By Steven Greenebaum

It took me fifty years, not so much to find myself and embrace what I wanted to do with my life but to discern how I might actually go about it. I was born just a few years after World War II, and most particularly for me that meant born just after the Shoah (Holocaust). I was a Jew, born into the relative safety of the United States. Still, the magnitude of the Shoah and the relentless hate it represented was shattering. I also learned that where Jews were allowed to live was limited “even” in the United States. There was something called “restrictive covenants” which could legally prevent a person from renting or selling a house to Jews. Once these were outlawed, “restrictive covenants” were followed by less formal but still onerous “gentlemen’s agreements.” My childhood was spent in the Fairfax area of Los Angeles, a place where Jews were allowed to live. The injustice of it was squarely in my face.

It was when I approached my teens that I learned that injustice was far more widely spread. “Restrictive covenants” and “gentlemen’s agreements” not only outlawed Jews from neighborhoods but also Blacks. I was an avid reader and my reading soon taught me at least some of the history of the mistreatment of Native Americans as well. This was another stark reminder that facing injustice was clearly not just a Jewish concern.

By the time I was off to college, I felt called to do something. I needed to do something. Something. But what? The issue of racial and religious injustice seemed so deeply and firmly embedded in our culture. What on Earth could I do? As yet I had no clue.

As a youth in religious school (every Sunday during my grade-school years), I had been taught that God was a God of love and justice. Really? If so, where the heck was God? Then the Reverend Dr. King began to lead marches protesting bigotry – bringing to public awareness those who were suffering from the injustice of racism. It made sense to me that Dr. King was a minister. The God I believed in was a God of love and justice, and here was a man of God leading a scrupulously non-violent movement against hate and injustice. Yes! Then Dr. King was assassinated. Where was God’s justice hiding? Over the years there were numerous other untimely deaths of people striving for justice.

I spent the next decades bouncing from one job to another. I taught classes in colleges. I taught classes in high schools. I briefly wrote scripts for Hollywood. I went back to school (thanks to a lovely scholarship) and got an MA in Music. Now I also directed choirs – in both churches and synagogues. To be clear, it’s not that I didn’t enjoy myself or make a decent living. And yes, justice remained crucial. But while I gave time to various nonprofit causes, nothing stuck. My life still had no direction.

I met a wonderful Chicana. We fell in love, decided to marry, and planned our life together. She was not only wonderfully independent but also deeply dedicated to justice – particularly but not solely for Chicanos (these days the word is typically Latinos). Here was yet another group suffering from bigotry and injustice. She seemed so incredible and perfect. But before we could marry, before she could live the giving life she so looked forward to, she was killed a traffic accident. Yet again, where was justice?

Injustice seemed to pile upon injustice, for both people I knew and people I read about. This is certainly not the place to chronicle the whole of it, but in 1999, at age fifty, I hit the wall.

God was a God of justice? Then where was God? Why was God hiding? For several months, both silently and aloud, I angrily demanded/prayed, “God, if you’re there, I want answers!!” Then, at last, a quiet inner voice told me to get a pen and paper and write. So I did. I took dictation – three pages of it! That dictation gave me both guidance and then purpose to my life. It made it clear that humanity was one family – but that family delighted in dividing itself. A particularly hateful way of dividing ourselves was by our spiritual traditions. This gave me my calling. Interfaith.

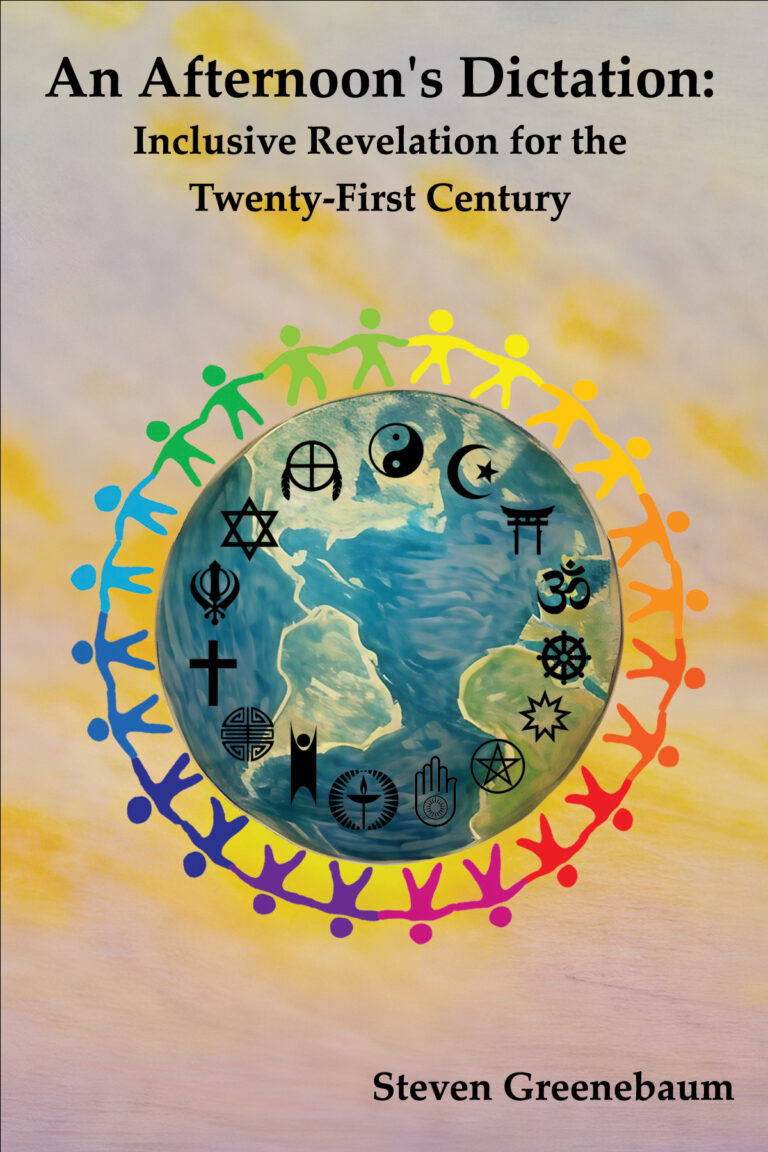

Of course, that change of direction did not happen overnight. I spend several years studying that afternoon’s dictation. Then I went back to school, this time studying ministry, became an Interfaith minister, and founded the Living Interfaith Church. But preaching from the pulpit how and why we should respect our spiritual diversity wasn’t enough. I wrote my first book, “The Interfaith Alternative” (published in 2012). My second book, “Practical Interfaith,” was published in 2014. My third book, a spiritual memoir titled “One Family: Indivisible,” was published in 2019. I had fully intended “One Family: Indivisible” to be my last book. But after it was published, I realized there needed to be one more, a final book to pull it all together – not only to share fully the dictation I had taken but what I’d made of it after years of study. NOT that I in any way believed or believe that mine should be the final word; but I did believe that a discussion needed to start. So I wrote “An Afternoon’s Dictation”. It’s available for pre-order now and will be published June 1st.

What’s “An Afternoon’s Dictation” about and why was it necessary for a seventy-three-year-old man in ill-health to write it?

It was not lost on me that while my demands for answers had been about justice, the first sentences of the dictation were about religion. “Religion is but a language for speaking to Me. Think ye that arbol is ‘better’ than tree? Was Old English a ‘false language’ because you now speak modern English?” Then later, “Seek truth in the commonality of religions.” My questions about justice were indeed addressed later. But these were front and center. Wrapping my mind around “Religion is but a language for speaking to Me.” took some time. But in the end it made sense.

Guided by “Seek truth in the commonality of religions” I began a study of our diverse religions, but not until I spent a good deal of time reading, rereading and pondering the whole of the dictation. As I explored our religions, the same truths kept popping up, though varying widely in how they were expressed in differing cultures, eras, and religious traditions. These truths are what I try to give voice to in the book.

I did re-order the dictation for “An Afternoon’s Dictation” (not rewrite it, just re-order it for clarity of topic). As I looked at it and studied it, there seemed to me to be five deeply related but separate subjects. These five subjects became the essential sections of my book.

The first two sections are titled “The Call of Interfaith” and “Dealing with Death and Dying”. These two not only clarified how we might appreciate our differing traditions, rituals, and scriptures, but also gave me a much more comfortable handle on dealing with the darkness of death. It required years of study, but as I learned more and more of the mutual truths to be found in our diverse traditions, it became clear to me that the path for the remainder of my life must be Interfaith.

That said, for me the crucial sections of the book are “The Call to Love,” “The Call to Justice,” and “The Call to Community.” I found these calls expressed in tradition after tradition. In each section I quote from tradition after tradition just how important these calls are.

And in studying these three topics I realized something else. They are connected. Yes, we are called by all of our traditions to be loving. But there can be no love without justice. We are called by all of our traditions to act with justice. But there can be no justice without humble community. Trying to achieve love and justice while still endlessly dividing ourselves into categories of “us” and “them” won’t work. It has never worked. The lack of humility to be found in our divisions has undermined our pursuit of justice. The lack of both community and justice has undermined our pursuit of love – even though all our spiritual traditions cry out for it.

The hope of “An Afternoon’s Dictation” is that our human family might find a means to move out of the darkness we have made of our world. Clearly, one book cannot magically change things. But perhaps it may help point us in a positive direction – if we will study the dictation as well as how completely our diverse spiritual traditions have embraced the calls of love, justice, and humble community (too often preached while ignored at the same time). The call to Interfaith is the call to act with love, justice, and in community with humanity – not simply to believe it or preach it but to ACT.

But what might others feel about this? An advance review copy of “An Afternoon’s Dictation” was sent to a rabbi, an imam, and a priest, seeking to obtain an interfaith response to my work and, most especially, the book. Here are their responses, for which I am most grateful.

“In An Afternoon’s Dictation, Interfaith teacher Rev. Steven Greenebaum shares his spiritual journey. He tells of his encounter with Cosmic Conscience, first through revelation and then through study. Over the years, he learned why love, justice, and humility are at the ethical core of all spiritual traditions. Writing with exceptional clarity and warmth, he invites us to find our own moral center.” Rabbi Laura Duhan-Kaplan, Director of Inter-Religious Studies, Vancouver School of Theology.

“The author’s reflections in this unique book are profound and soulful. Steven Greenebaum is the embodiment of the truth that Interfaith is not about religious conversion but about human transformation. Through Interfaith we become more fully human; we evolve into the fullness of our being. This is a critical message for our polarized times.” Imam Jamal Rahman, author of Spiritual Gems of Islam.

“Rev. Steven Greenebaum has dedicated his life to interfaith ministry, not just thinking, dialoguing, or writing about it but living it in action and community. In An Afternoon’s Dictation, he shares the inclusive ‘revelations’ that compelled him to pursue this boundary-breaking work. Religion is a crucial development in the evolution of human consciousness, but in today’s world, religious experience is in crisis – a time of breakdown and breakthrough. Interfaith living is its horizon of hope. Greenebaum’s legacy will continue to grow as that horizon expands into a share future. Father John Heagle, Catholic priest and author of Justice Rising: The Emerging Biblical Vision.

I am not so arrogant as to believe that my work will change the world. But I do believe that if we will share and study the dictation, we just might be able to move down the path of respecting our diversity and reconcile our so very divided human family.